DMX Dead at 50

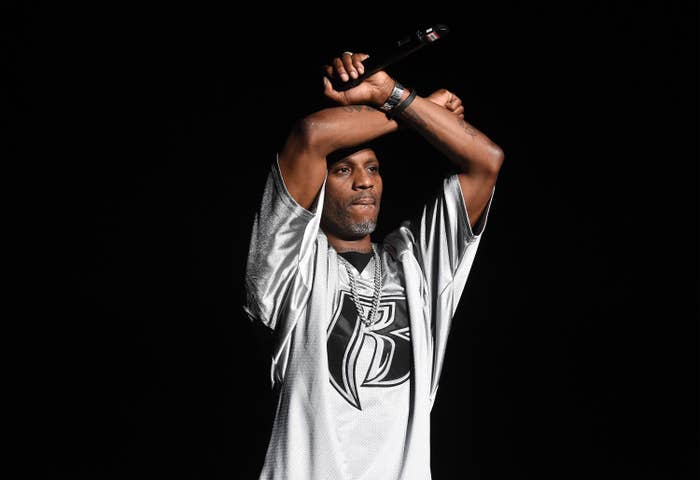

DMX performs onstage during the Bad Boy Family Reunion Tour at the Forum on Oct. 4, 2016, in Inglewood, California.

Earl Simmons, the performer known to the world as DMX, has died a week after he was taken to a New York hospital, his family told media. He was 50.

The rapper and actor was hospitalized in White Plains late Friday, April 2, after he had a heart attack, his attorney and friend Murray Richman told media. TMZ reported that DMX had overdosed.

“Earl was a warrior who fought till the very end,” his family said in a statement to People magazine. “He loved his family with all of his heart and we cherish the times we spent with him. Earl’s music inspired countless fans across the world and his iconic legacy will live on forever. We appreciate all of the love and support during this incredibly difficult time. Please respect our privacy as we grieve the loss of our brother, father, uncle and the man the world knew as DMX.”

The family said they would release information about his memorial service at a later time.

The Grammy-nominated hip-hop star, best known for his barking style on hits like “X Gon’ Give It to Ya” and “Party Up (Up in Here),” had been open about his experiences with drug addiction, recounting in 2020 how he had first been tricked into smoking crack when he was just 14. In 2019, he checked himself into rehab.

“I learned that I had to deal with the things that hurt me. I didn’t really have anybody to talk to,” he said in an interview. “In the hood, nobody wants to hear that. … Talking about your problems is viewed as a sign of weakness when actually it’s one of the bravest things you can do.”

After a childhood marked by physical abuse, parental abandonment, and run-ins with police, DMX found music as a teenager while living in a group home. His stage name was taken from the DMX digital drum machine.

After he signed with Def Jam, he released his first major label single, “Get at Me Dog,” in 1998, and his album It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot followed months later, debuting at No. 1 and going on to sell millions of copies. Two decades later, Pitchfork included it among its list of that year’s best albums, describing it as “full of … zealous storytelling, unglued theatrics, and inexorable nihilism.”

The album also contained the single “Ruff Ryders’ Anthem,” declared by VH1 in 2008 to be among the 100 greatest hip-hop songs ever. As DMX gained popularity, his managers spun off into their own label, Ruff Ryders Entertainment, which became something of a hip-hop family or crew for acts like Eve and MC Jin.

DMX’s second album, Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood, was also released in 1998 and went triple platinum. The cover featured DMX covered in blood, staring solemnly at the camera. “DMX’s canine split personality flow is like none other,” declared the AllMusic review, “not only rhyming over tracks, but barking expression over explosive beats.”

During his career, DMX released eight studio albums and was nominated three times for a Grammy Award, including Best Rap Album for his third album, … And Then There Was X, which contained the hit single “Party Up (Up in Here).” In 2000, he was named Favorite Rap/Hip Hop Artist at the American Music Awards.

He also starred as a nightclub owner in the 2000 Jet Li action film Romeo Must Die alongside R&B singer Aaliyah, who died the following year. A New York Times reviewer declared the movie “scattered,” but said DMX emerged as a star. “He establishes so much audience rapport in his brief time onscreen that the film suffers from his absence,” the reviewer wrote.

During his life, DMX was also arrested or jailed on a number of charges, from drug possession to animal cruelty. In 2018, he was sentenced to a year in prison for tax evasion. Ahead of that sentencing, his autobiographical 1998 song “Slippin’” was played in court so the judge could hear about his troubled life.

Throughout his life, DMX fathered 15 children with nine different women.

When news of his hospitalization was revealed, artists like Missy Elliott, SZA, Chance the Rapper, and Ja Rule (with whom DMX had once feuded) all expressed their sadness on social media — a sign of DMX’s broad influence.

His AllMusic biography describes him as having taken the throne, after the deaths of Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G., as the “undisputed reigning king of hardcore rap” who used his songs to explore spiritual anguish and street life, the sacred and the profane.

“See, to live is to suffer,” DMX said in “Slippin’,” “but to survive — well, that’s to find meaning in the suffering.”