Crazy Facts About Freddie Mercury That Were Left Out Of Bohemian Rhapsody

Besides simple facts like Freddie was in 2 bands before Queen.

It took over a year before he thought up the name Queen

He went by his real name Farrokh Bulsara up until he changed the bands name to Queen

Born Farrokh Bulsara in the British protectorate of Zanzibar, Freddie’s oversized talent was matched only by his flamboyance and exuberance. These qualities merged to create masterpieces of the group’s songbook, and some of the greatest live performances on record. In life, his four-octave voice – since studied by scientists in an attempt to unlock the secrets of its intricacies and awesomeness – raised the bar for what a rock singer could be. In death, he gave voice to the millions suffering from AIDS.

In honor of the 25th anniversary of his passing, here are some lesser-known elements of Mercury’s incredible legacy.

He released a pre-Queen solo single covering the Ronettes and Dusty Springfield – and mocking Gary Glitter.

While Mercury’s first appearance on vinyl predates any release from Queen, it does feature two of his bandmates and a characteristic dose of irreverence. In early 1973, the fledgling band was recording its debut album at London’s Trident Studios, a cutting-edge facility that had recently been utilized by David Bowie and the Beatles. Though it was an honor to follow in such prestigious footsteps, Queen’s lowly status meant that they were only allowed to record during off-peak hours: usually between 3 and 7 a.m. “They were given what was called ‘Dark Time,’” producer John Anthony told band biographer Mark Blake in Is This the Real Life? The Untold Story of Queen. “That’s when an engineer can produce his favorite band or a tea boy can be used as a tape op.”

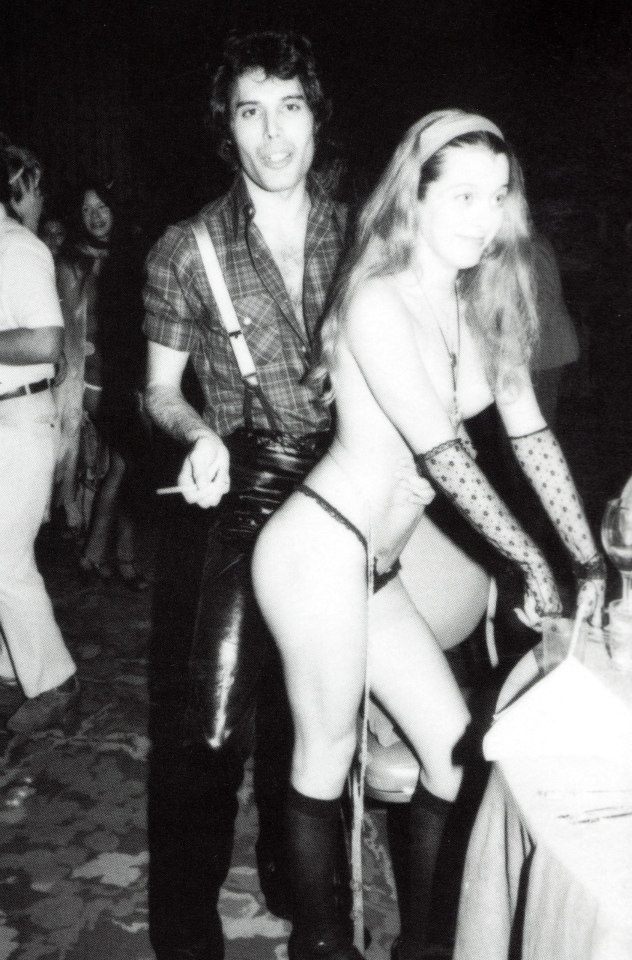

There was a party with dwarves carrying trays of cocaine on their heads

“[Freddie] could out-party me,” one-time fellow coke-fiend Elton John told Uncut in 2001, “which is saying something.” Queen were well-known in the industry for their outrageous shindigs. Most notable was the ‘Jazz’ launch party at New Orleans’ Fairmont Hotel in 1978, which featured wholesome delights including nude waiters and waitresses, a fellow biting heads off live chickens, naked models wrestling in a liver pit and dwarves swanning about with trays of cocaine strapped to their heads. Standard.

One night, while waiting for their studio to become free, Mercury was approached by Trident’s house engineer, Robin Geoffrey Cable. Cable had been trying to recreate record producer Phil Spector’s famed “Wall of Sound” style, and felt that the Queen singer’s voice would be a perfect addition to the project. Mercury then enlisted the musical services of Brian May and Roger Taylor, and together they recorded covers of the Ronettes’ “I Can Hear Music” (then recently revitalized by the Beach Boys) and Carole King and Gerry Goffin’s “Goin’ Back,” made famous by Dusty Springfield.

The results were deemed adequate and Cable suggested readying the tracks for release. Mercury agreed, but with Queen’s debut nearing completion, he insisted on using a pseudonym to avoid confusing the public. He settled on the outlandish name Larry Lurex, which he admitted was a “personal piss-take” on Gary Glitter, who ruled the British charts at the time. The surname was borrowed from a brand of metallic yarn used in bodysuits favored by Glitter and the glam-rock elite.

Glitter – still decades away from disgrace and incarceration for sex crimes – wielded a massive army of fans, none of whom appreciated Mercury’s jab. They refused to buy the song out of spite, and many DJs declined to play it. Larry Lurex’s one and only single sank like a stone when it was released in late June. Queen’s first album, released just a week later, performed somewhat better.

Though Mercury continued to funnel his energy into the band, he was miffed on principle by Larry Lurex’s failure. “I thought it was great!” he said later. “Let’s face it, it’s the highest honor for any performer to have people copying you. It’s a form of flattery and it was only meant in fun. Anyway, what does it matter? After Elvis Presley, it’s all parody, isn’t it?”

Freddie got up Jacko’s nose

In the early ’80s we could’ve seen all manner of Mercury/Michael Jackson collaborations. Jackson was a big Queen fan and the pair had become pals, to the point of recording together at Jackson’s California mansion. They worked on ‘Victory’ and ‘State Of Shock’, the former unreleased (but also the title of The Jacksons’ 1984 album), the latter eventually recorded by The Jacksons and Mick Jagger when Mercury couldn’t give up the time. Then there was ‘There Must Be More To Life Than This’, once slated for Queen’s 1982 album ‘Hot Space’ but eventually surfacing (without Jackson) on Mercury’s 1985 solo debut ‘Mr. Bad Guy’. A version with Jackson finally appeared on Queen’s 2014 cash-rinser ‘Queen Forever’. Why’s this a quintessential Mercury story? Because the beautiful partnership fell to bits one day when Jackson walked into the lounge and found Mercury snorting cocaine through a $100 bill. Old habits.

He built a stage for David Bowie, and sold him a pair of vintage boots.

Bowie and Mercury famously joined forces on the worldwide smash “Under Pressure” in 1981, but their relationship actually stretched back to the late Sixties, when both were relative unknowns. Bowie had slightly more clout at the time, and was booked to play a small lunchtime set at Ealing Art College. A fascinated Mercury followed him around, offering to carry his gear. Bowie soon put him to work pushing tables together as a makeshift stage.

Not long after, Mercury and Roger Taylor opened a stall at Kensington Market, where they sold vintage clothing to supplement their meager income from music. “We got into old Edwardian clothes,” Taylor told Blake. “We’d get bags of silk scarves from dodgy dealers. We’d take them, iron them, and flog them.” Brian May recalls being less impressed by the quality of clothes. “Fred would bring home these great bags of stuff, pull out some horrible strip of cloth and say, ‘Look at this beautiful garment! This is going to fetch a fortune!’ And I’d say, ‘Fred, that is a piece of rag.’”

Mercury and Taylor were not well suited to run their own business, and the kindly Alan Mair, who managed the clothing stall across the aisle, ultimately hired them. “He was always efficient, he was very polite,” Mair said of Mercury in the BBC documentary Freddie’s Millions. “No one ever complained about him, he never had any attitude problems. He always got there a bit later, but that didn’t matter.”

Mair was a mutual acquaintance of Bowie’s early manager, and one day the future Starman himself wandered into their stall. “‘Space Oddity’ had been a hit, but he said he had no money,” Mair says in Is This The Real Life. “Typical music biz! I said, ‘Look, have them for free.’ Freddie fitted Bowie for the pair of boots. So there was Freddie Mercury, a shop assistant, giving pop star David Bowie a pair of boots he couldn’t afford to buy.”

He rode around on Darth Vader’s shoulders

At the height of Star Wars-mania in 1979 and 1980, Mercury commemorated the movie in the only way that made sense: stalking the stage for encore performances of ‘We Will Rock You’ perched on Darth Vader’s shoulders. Well, it was probably a roadie, but you get the picture. US photographer Tom Callins was one of those who did: “It was pandemonium. Everybody just thought it was so funny, so Freddie. It was so over-the-top.” And presumably Mercury came ‘fresh’ from one of the quickies he reputedly had between main show and encore, and sometimes even between songs.

. He was prime subject for all the old chestnuts of rock mythology

One of the tales buzzing around Mercury was the old chestnut about employing a coterie of groupies to take turns blowing cocaine up his arse, with the unusual route causing such havoc in his bowels long-term that he had to keep pelting to the loo. This may be a case of putting the cart before the horse. It may also be mixed up with the myth about Stevie Nicks. Another attached to him was the well-worn classic about having a rib removed so he could cut out the middle man and orally pleasure himself, but seeing as this one’s been rolled out for – among others – Prince and Marilyn Manson, it should probably be taken with a pinch of salt. Unless they’re all at it.

He accidentally gave the Sex Pistols their big break – and probably regretted it.

On December 1st, 1976, Queen was booked on the early evening talk show Today with Bill Grundy to promote their upcoming album, A Day at the Races. But when Mercury had to make a visit to the dentist – apparently his first in 15 years – EMI, the band’s label, sent their new signing: the Sex Pistols. The free drinks thoughtfully provided backstage by the television producers ensured that the unruly punks were in especially naughty form. Egged on by a combative Grundy, who was supposedly just as drunk as they were, Steve Jones and John Lydon (a.k.a. Johnny Rotten) both uttered numerous obscenities on air, including the unforgivable “fuck.”

Even though the program only broadcast in the Greater London area, the swift backlash in the press vaulted the Sex Pistols into the national spotlight. “The Filth and the Fury!” screamed the front-page Daily Mirror headline, and numerous other tabloids followed suit. According to legend, one particularly outraged truck driver smashed his television set. Conservative members of the London City Council described the Sex Pistols as “nauseating” and “the antithesis of humankind.” Many dates on their imminent Anarchy Tour of the U.K. were canceled or protested, but the media scrutiny only increased their popularity.

The Sex Pistols, as a rule contemptuous of superstar bands, held particular disdain for the pomp, pageantry and virtuosity of Queen. And the feelings were apparently mutual. Mercury was never a fan of their rough-edged brand of rock. “He told me he didn’t understand the whole punk thing,” an EMI executive told Blake. “That wasn’t music to him.”

Their paths would overlap in 1977 at London’s Wessex Studios, where the Sex Pistols were recording their debut. “We used to bump into them in the corridors,” May recalled to Blake. “I had a few conversations with John Lydon, who was always very respectful. We talked about music.”

But Roger Taylor was much less complimentary about the band’s bassist. “Sid [Vicious] was a moron. He was an idiot,” he remembered in the documentary Queen: Days of Our Lives. On one memorable occasion, Vicious drunkenly wandered into Queen’s studio and tried to pick a fight with Mercury by snarling: “Have you succeeded in bringing ballet to the masses yet?” – a reference to a particularly flamboyant boast the singer had made in a recent NME interview.

Mercury was not so easily rattled. “I called him ‘Simon Ferocious’ or something and he didn’t like it at all,” he claimed later in a television interview. “I said, ‘What are you going to do about it?’ And he had all these [cuts] – he was very well marked – so I said, ‘Make sure to scratch yourself in the mirror properly today because tomorrow you’re going to get something else.’ He hated that I could even speak like that. I think we survived that test.”

He performed with the Royal Ballet Company.

The Sex Pistols couldn’t have known it, but soon Mercury would make good on his avowal to bring ballet to the masses. In August 1979, Royal Ballet principle Wayne Eagling went looking for a particularly limber star to join their ranks for a charity gala performance. After Kate Bush turned them down, Eagling turned his attention to Mercury.

Though his initial reaction was less than favorable (“I thought they were mad!”), he eventually warmed to the idea after speaking to the head of EMI, Sir Joseph Lockwood, who also happened to be the chairman of the Royal Ballet board of governors. “Freddie had a general interest in the ballet, but Lockwood really got him fired up,” said Queen manager John Reid in The Great Pretender. “He was fascinated by the scale. It was epic. And everything about Freddie’s performance was epic.” It was a perfect match.

Despite Mercury’s athletic performances with Queen, it would take intense rehearsals to get him up to par. “They had me practicing at the barre and all that, stretching my legs … trying to do things in a week that they’d been doing for years,” he told The London Evening News. “It was murder. After two days I was in agony. It was hurting me in places I didn’t know I had, dear.”

Mercury made his grand debut on Saturday, October 7th, 1979, at London’s Coliseum Theater before 2,500 patrons. He sang “Bohemian Rhapsody” and Queen’s upcoming single, “Crazy Little Thing Called Love,” to live orchestral backing, all while being hoisted aloft by three shirtless men. By the end of the performance he donned a silver bodysuit, and executed several formidable full-body flips.

“There was only one person in the world that could have gotten away with it,” Roger Taylor, who was in the audience, told Blake. “Freddie was performing in front of a very stiff Royal Ballet audience, average age 94, who did not know what to make of this silver thing that was being tossed around onstage in front of them. I thought it was very brave and absolutely hilarious.”

He dressed Lady Diana in drag and snuck her into a gay club.

By the mid-Eighties, Queen’s proximity to royalty went well beyond their name. Mercury had become a friend of Lady Diana Spencer, then the Princess of Wales. The so-called “People’s Princess” had endeared herself to a nation with her down-to-earth manner, but the constant media harassment was a tremendous strain on the young royal. So Mercury conspired to give her a night on the town.

According to a 2013 memoir by actress Cleo Rocos, Diana and Mercury spent the afternoon at English comedian Kenny Everett’s home, “drinking champagne in front of reruns of The Golden Girls with the sound turned down” and improvising dialogue with “a much naughtier storyline.” When Diana inquired about their evening plans, Mercury said they were planning to visit the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, one of the most iconic gay venues in London. The princess insisted that she come along and blow off some steam.

The Royal Vauxhall was well known for its rough crowd, and fights often broke out between patrons – perhaps not the best place for a princess. “We pleaded, ‘What would be the headline if you were caught in a gay bar brawl?’” writes Rocos. “But Diana was in full mischief mode. Freddie said, ‘Go on, let the girl have some fun.’”

A disguise was essential to the plan’s success, so Everett donated the outfit he had planned to wear: an army jacket, dark aviator sunglasses and a leather cap to conceal her hair. “Scrutinizing her in the half light,” Rocos continues, “we decided that the most famous icon of the modern world might just – just – pass for a rather eccentrically dressed gay male model.”

The group managed to sneak Diana into the bar undetected. The crowd, distracted by the presence of Mercury, Everett and Rocos, ignored the Princess completely, leaving her free to order drinks for herself. “We inched through the leather throngs and thongs, until finally we reached the bar. We were nudging each other like naughty schoolchildren. Diana and Freddie were giggling, but she did order a white wine and a beer. Once the transaction was completed, we looked at one another, united in our triumphant quest. We did it!”

Not wishing to push their luck, they left only 20 minutes later. But for Diana, the brief chance to shed the weight of celebrity was precious. “We must do it again!” she enthused as they made their way back to her home at Kensington Palace.

Following Mercury and Everett’s AIDS-related deaths in the early Nineties, Diana became the patron of the National AIDS Trust, one of the U.K.’s leading organizations devoted to the illness. Their night at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern was turned into a 2016 musical, which was performed at the venue.

He recorded songs with Michael Jackson, but the King of Pop’s pet llama interrupted the sessions.

Mercury’s love of Michael Jackson dates back to his pre-Queen days, when he would loudly sing the praises of the Jackson 5’s “I Want You Back” to his hard rock-loving roommates. “Freddie was in awe of Michael,” his personal assistant Peter Freestone told Blake. When Jackson scaled new artistic and commercial heights with his chartbusting Thriller in 1982, it seemed like the perfect time for the King of Pop and the Queen frontman to join forces.

Mercury traveled to Jackson’s home studio in Encino, California, in the spring of 1983 to begin work on three demos. “There Must Be More to Life Than This,” which had its genesis during sessions for Queen’s 1982 album, Hot Spaces, lacked a complete set of lyrics, and Mercury can be heard encouraging Jackson to ad lib on session tapes. “State of Shock” was a tune that Jackson had composed largely on his own, whereas “Victory” was co-written by the two men.

Bootlegs of the demos reveal strong efforts, though they were ultimately left incomplete. A revised version of “There Must Be More to Life Than This” saw inclusion on Mercury’s 1985 solo album, Mr. Bad Guy, while “State of Shock” was issued as a 1984 single by the Jacksons featuring Mick Jagger. The track “Victory” remains in the vault to this day.

Publicly, Mercury was very diplomatic in explaining exactly why the partnership failed to flourish. “We never seemed to be in the same country long enough to actually finish anything completely,” he said in 1987. But another interview from the same period belayed hints of frustration with the King of Pop. “He simply retreated into his own little world. We used to have great fun going to clubs together but now he won’t come out of his fortress and it’s very sad.”

According to Queen’s manager, Jim Beach, Jackson’s idiosyncrasies, which have since been well documented, began to grate on Mercury in the studio. “I suddenly got a call from Freddie saying, ‘Can you get on over here? Because you’ve got to come get me out of this studio,’” he revealed in The Great Pretender. “I said, ‘What’s the problem?’ And he said, ‘I’m recording with a llama. Michael’s bringing his pet llama into the studio everyday and I’m really not used to recording with a llama. I’ve had enough and I’d like to get out.’”

Jackson, for his part, may have had issues with Mercury’s quirks, too. According to a story sold to The Sun by Mercury’s former personal assistant, sessions broke down when Jackson caught his singing partner snorting cocaine through a hundred-dollar bill.

In any event, Mercury remained prickly about the failed collaboration for the rest of his life. “Fred came out of it all a little upset because some of the stuff he did with Michael got taken over by the Jacksons and he lost out,” says May in Is This the Real Life. A duet version of “There Must Be More to Life Than This,” revamped by producer William Orbit, was issued on the 2014 Queen Forever compilation. The other two titles remain unreleased.

He insisted that his final resting place remain secret, and the location is a mystery to this day.

Mercury was diagnosed with AIDS during the spring of 1987 and slowly began telling those close to him about his condition. “He invited us over to the house for a meeting and he just told us the absolute facts – the facts that we were starting to realize ourselves, anyway,” Taylor said in the documentary Freddie Mercury: The Untold Story. Mercury’s increasingly frail appearance and gaunt figure increased media speculation that something was terribly wrong with the seemingly indestructible frontman, but the group closed ranks and vehemently denied any problems. “We hid everything. I guess we lied! Because we were trying to protect him,” says May in Days of Our Lives.

By the end of 1990, the band completed Innuendo, which featured the melancholy ballad “These Are the Days of Our Lives.” Though it doesn’t directly address Mercury’s physical decline, the song casts a wistful eye toward Queen’s younger days. Fears for his health were made exponentially worse by the music video, shot on May 30th, 1991. The decision to shoot in black and white did little to disguise the extent to which AIDS had ravaged Mercury’s body. “He spent hours and hours in makeup sorting himself out so it’d be OK,” May told The Independent in 2011. “He actually says a kind of goodbye in the video.” Wearing a custom-made vest depicting each of his beloved cats, the final scene shows him staring down the camera with a wry smile before uttering, “I still love you.” These were to be his last words on camera.

Several weeks before filming, Mercury had been in Montreaux, Switzerland, recording as much as music as his weakened state would allow. According to May, the experience provided Mercury with a badly needed sense of normalcy. “Freddie at that time said, ‘Write me stuff. I know I don’t have very long. Keep writing me words, keep giving me things – I will sing, and then you can do what you like afterwards and finish it off,” he says in Days of Our Lives.

Producer Dave Richards noted a sense of urgency in the sessions. Gone were the days of spending hours fine-tuning instrumentation. “He was dying when he did those songs, and he knew he would be dead when they were finished because he said to me, ‘I’m going to sing it now because I can’t wait for them to do music on this. Give me a drum machine and they’ll finish it off.’”

May wrote him “Mother Love,” a slow-burning epic that Mercury tackled with his usual gusto. “I don’t know where he found the energy,” May later told The Telegraph. “Probably from vodka. He would get in the mood, do a little warm-up then say, ‘Give me my shot.’ He’d swig it down ice cold. Stolichnaya, usually. Then he would say, ‘Roll the tape.’” Unable to stand for long periods and forced to walk with a cane, Mercury tracked vocals for “Mother Love” in the control room.

“We got as far as the penultimate verse and he said, ‘I’m not feeling that great, I think I should call it a day now. I’ll finish it when I come back, next time.’ But, of course, he didn’t ever come back to the studio after that.” On the final version, May sings the last verse of the song himself.

Mercury retreated back to his Garden Lodge home after that, drawing support from Jim Hutton and Mary Austin – his former girlfriend, whom he first met in 1970. They had lived together for seven years, and though they no longer shared a home, they still shared each other’s lives. In interviews he consistently referred to her as his one true friend, and once told journalist David Wigg that when it came to his will, “I’m leaving it all to Mary and the cats.” The delicate Queen classic “Love of My Life” is written in her honor.

Austin watched as she saw her soulmate’s flame dim. “He’d given himself a limit, and I think that when he couldn’t record anymore or have the energy to, it would be the end,” she said in The Great Pretender. “Because his life and his joy had been that. And I think without it, he wouldn’t have been strong enough to face what he had to face.”

Now forced to confront the inevitable, Mercury began to make tentative arrangements for his death. “He suddenly announced one day after Sunday lunch, ‘I know exactly where I want you to put me. But no one’s to know, because I don’t want anyone to dig me up. I just want to rest in peace.’”

When Mercury succumbed AIDS-related bronchial pneumonia on November 24th, 1991, his body was cremated at Kensal Green cemetery in West London. His ashes were kept in an urn in Austin’s bedroom for two years before she quietly took his remains to their final resting place. “I didn’t want anyone to suspect that I was doing anything other than what I would normally do. I said I was going for a facial. I had to be convincing. It was very hard to find the moment,” she told The Daily Mail in 2013. “I just sneaked out of the house with the urn. It had to be like a normal day so the staff wouldn’t suspect anything – because staff gossip. They just cannot resist it. But nobody will ever know where he is buried because that was his wish.”

Apparently even Mercury’s parents have been kept in the dark about the location, but that hasn’t stopped fans from trying to find the place to pay their respects. Some have speculated that he’s in his native Zanzibar, while others believe him to be beneath a cherry tree in the garden of his mansion.

It seemed like the mystery was solved in 2013, when a plinth bearing Mercury’s birth name and birth date was discovered at Kensal Green. “In Loving Memory of Farrokh Bulsara, 5 Sept. 1946 – 24 Nov. 1991,” it read, “Pour Etre Toujours Pres De Toi Avec Tout Mon Amour – M.” The French translates to “Always to Be Close to You With All My Love,” and many speculate that the “M” in question is for Mary Austin.

And he wasn’t the person you think…

He was naturally shy. No, come back. According to friends, the Mercury on-stage was just a preposterous, outlandish act, although that doesn’t quite explain the orgies and insatiable appetites of one hue or another. Perhaps that was a pretty audacious coping mechanism. Truth is, away from the stage and the gossip, Mercury was a closed book. Roger Taylor and Brian May were the principal mouthpieces, Mercury the image, everything behind him opaque. Lyricist Tim Rice – who wrote with Mercury on 1988’s ‘Barcelona’ album – and Mercury’s PA Peter Freestone both insist ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ was his ‘coming out’ song. But no one ever realised.

In the colossal Imperial Ballroom inside the Fairmont New Orleans, Freddie Mercury—expert partier who lived by the mantra “excess all areas”—overwhelmed 400 guests at the launch of Queen’s seventh album, Jazz. This party had it all: “voluptuous strippers who smoked cigarettes with their vaginas, a dozen black-faced minstrels, dwarfs, snake charmers, and several bosomy blondes who stunned party revelers by peeling off their flimsy costumes to reveal that they were, in fact, well-endowed men,” it was described in Pamela Des Barres’s Rock Bottom: Dark Moments in Music Babylon.

It was Halloween 1978. The ballroom was outfitted with 50 dead trees rented especially for the occasion, which made it look like “a skeletal forest. It had a kind of witchcraft theme,” said EMI’s Bob Hart. Bourbon Street’s biggest freaks and eccentrics were hired to entertain, leaving other bars and clubs forced to close for the night.

Mercury et al arrived preceded by the Olympia Brass band and flanked by snake charmers and strippers dressed as nuns. Between sips of the finest champagne, a bill that would later tally an alleged $200,000, music execs could enter a back room where they would receive sexual favors. “Most hotels offer their guests room service,” Mercury told one publication. “This one offers them lip service.”